Posted on October 04 2020

"Riot Grrrl Convention 1992" By RockCreek, licensed under CC BY 2.0

"Riot Grrrl Convention 1992" By RockCreek, licensed under CC BY 2.0

ZINES AND FEMINISM ARE AN INTERLINKED PHENOMENON, DIRECTLY INFLUENCING HOW FEMINISM WORKS AND APPEALS TO WOMEN TODAY.

By Sabrina Mei-Li Smith

Stinging like a chilli-impregnated Andrex, Zines are the hottest thing in academia right now. This art form reached its zenith in the mid-1990s but was replaced by a little ol’ thing called ‘The Internet’, so zines can’t have much cultural capital, right?

Zines and feminism are an interlinked phenomenon, directly influencing how feminism works and appeals to women today. Of course, feminism is important, more so than in other times as a plethora of abuse scandals are unveiled by the #MeToo campaign, the Weinstein scandal, #WhyIStayed, #YouOkSis... I could go on. But the overarching ideas of feminism, outlined simply and effectively in Caitlin Moran’s 2011 book How to be a Woman (1. Do you have a vagina? 2. Do you want some sort of say over said vagina?), cascaded around American university towns in the 1980s and 1990s using the medium of Zines. You couldn’t go anywhere without picking up a fistful of these scruffy little homemade things that detailed anything and everything about how to be a feminist, how to be an eco-warrior, what was LGBTQ+, and how to recognise privilege and not be a douchebag.

"BikiniKBrixt110619-14" By Ralph_PH, licensed under CC BY 2.0

"BikiniKBrixt110619-14" By Ralph_PH, licensed under CC BY 2.0

‘Riot Grrrl Revolution Now’ was a slogan on fliers, T-Shirts, posters, and zines. It encompassed an artistic and stylistic movement. It wanted to level the playing field so women could express themselves in the same way men had been doing for decades. It was an appropriation of Bikini Kill’s ‘Revolution Grrrl Style Now’ album and the Olympia scene that encouraged Bikini Kill to produce their first zine. It was a new beginning and influenced many more albums, bands, and zines.

So this was great if you lived in Olympia. A small network of likeminded women could get together against the patriarchy and communicate by DIY pamphlets; pamphlets that detailed personal stories of abuse at the hands of patriarchy. They challenged racism, classism, and homophobia, discussed feminism, debated anarchism, vilified rape and domestic abuse, praised female empowerment, and campaigned against vivisection and cruelty to animals. Zines spoke in an authentic voice, were lo-fi, cheap to photocopy, and distribute in the mail. They became the internet before ‘The Internet’ and could reach wider than Olympia, or even America.

ZINES WERE AN AMERICAN 'THING'. AN AMERICAN, YOUNG, WHITE WOMAN'S 'THING', AT THAT. HOWEVER, LIKE MOST ACCOUNTS OF COUNTERCULTURE, SCENES, OR MOVEMENTS, IT'S BEEN WHITEWASHED.

Zines created a thirst to reach out to individuals. Sometimes they reinforced how lonely the one activist in a small town could be. Readers of zines became creators but the problem of content arose – great, anybody can write these things but what do they write about? Do you write the word FEMINISM over and over again on every page? Dress it up in stories and poetry? Write about yourself and your own experiences? Just fill it with nude pictures? The form of creating a zine was cheap and easy (paper, biro, photocopier at the very least) but its relationship with content became hyper-personalised and reflective of women’s issues, rights, and personal stories. Lisa Crystal Carver’s RollerDerby and Pagan Kennedy’s Pagan’s Head became two zines that emerged in the late 1980s. Both lend themselves towards the personal style that would later influence the confessional nature of bestsellers like Elizabeth Wurtzel’s 1994 memoir Prozac Nation.

Zines were an American ‘thing’. An American, young, white woman’s ‘thing’, at that. However, like most accounts of counterculture, scenes, or movements, it’s been ‘whitewashed’. Many intersectional women created zines, leaning towards a more diverse pattern of voices. Indeed, a zine’s ease of self-production, the authenticity associated with lo-fi aesthetics, and ‘quirkiness’ became appealing for individuals who had something to say but little means to express themselves. For example, Sabrina Sandata’s Bamboo Girl spanned topics from reproductive rights to pop culture in one issue, all accompanied by hand-drawn illustrations about race, anti-imperialism, and disabilities.

Sabrina Sandata’s Bamboo Girl

Zines were quirky but they were most of all fun. Their poison pen fonts, biro cartoons, and pop culture references lent an air of playfulness to some of the weightier confessional features, and socio-political commentaries without detracting from issues. They made ‘highbrow’ concepts, discussed in the ivory towers of academia by (often) white male academics, accessible to a network of disaffected youth. Contextualising a mid-90s zine positions it alongside mainstream media outlets of tabloid papers (usually full of scaremongering right-wing trash), music magazines (heavily written by white, male journalists and featuring white male music), and mainstream TV (for example, the UK only had 4 channels), which marginalised any inklings of alternative lifestyles. In short, zines bridged the gap between mainstream media and academic discourse and opened up a whole world of ‘wokeness’ before being ‘woke’ was a thing.

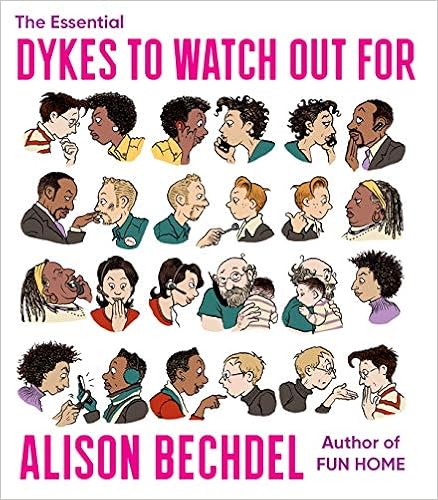

One of the best examples of zine ideas influencing academia and mainstream culture is from Alison Bechdel’s 1985 zine Dykes to Watch Out For. The Bechdel test has become a measure of the representation of women in fiction and is employed by colleges and universities on their arts and humanities-based degrees – and if it hasn’t, I’d want to know why not. Dykes to Watch Out For contained a comic strip that featured two women discussing the criteria by which they would watch a movie: 1. It has to feature at least 2 women, 2. Who talk about something, 3. Other than a man. When you apply the Bechdel test to favourite films or classic works of literature, you begin to see how under-represented women are in art and how much needed the reworking of accepted narratives is - and the invention of new narratives.

Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For

Zines were the lifeblood of the feminist movement in America and became a means for alternative and underground fans of bands in the UK to connect, since the punk zine Sniffin’ Glue emerged in the late 1970s. This fusion of music and feminism became the backbone of the 1990s ‘Britpop’ scene in the UK. Britpop borrowed musical styles and attitudes from decades past – The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, Bowie, The Sex Pistols... The Slits, The Ronettes, GirlSchool, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Joan Jett, Kate Bush... but these influences are forgotten. Zines, feminism, Riot Grrrl, and historical influences all shaped the formation of Britpop bands: Elastica, Lush, Echobelly, Daisy Chainsaw, Huggy Bear, Sleeper, PJ Harvey, Bjork, and Skunk Anansie are just a few female artists and women of colour who sang about feminist issues and thrived on exposure through their network of fanzines. All these bands have conveniently been ‘forgotten’, ‘whitewashed’ and ignored in favour of The BBC choosing to focus on 45 minutes of Blur and Oasis fighting an imaginary willy-waving competition, where one shouts ‘Manchester FC’ louder than ‘Chelsea FC’ (it may have been ‘West Ham’ vs. ‘Man City’ but I forget the details). Most of these female Britpop bands were products of transatlantic cross-pollination of ideas and ideology that came from the American zine scene, more so than the male contemporaries these bands toured with and jostled for space in NME against.

"Ladyfest craft fair" by dirty_black_chunks, licensed under CC BY 2.0

"Ladyfest craft fair" by dirty_black_chunks, licensed under CC BY 2.0

These female musicians influenced a new generation of girls who grew up with Britpop. By the time these early millennials reached their twenties in the early to mid-2000s, the internet was available in university halls and libraries and MySpace became the new Zine space, Blogger the new perzine and it seemed the end for old-style sticky tape and glue zine publications. However, the seeds were set for the Ladyfest movement to continue where feminist zines left off. Ladyfests came from small collectives of feminists putting on events for women artists and female-identifying musicians to play in a safe space – a grassroots ‘for women, by women’ initiative that had a DIY ethos to their city-based festivals. The evenings concentrated on music and performances with notable bands like Queen Adreena, StinkMitt, and Peaches playing larger Ladyfests. The daytimes focussed on workshops about activism, feminism, writing, music, art, theatre, and spoken word performances and, of course, zine-making. Most of all, they became part of a larger global network of likeminded feminists using the internet in the way zines functioned a decade past.

As the internet became a widespread means to cascade the messages of feminism, intersectionality, queerness, and disability activism, zines should have died a death. But, they haven’t. Feminist zines do still exist, zines that follow both established and new bands are still produced, and zines that concentrate on the ‘every day’, the ‘weird’, the ‘mundane’ have become ever more popular. Zines that feature personal stories, poetry, photography, art, geo-political issues, activism, and sports are readily bought and sold on eBay and at specialist collector fairs. They retain their scruffy, DIY form but their content can reach further than white feminist issues, bordering onto local grassroots initiatives, interviews, queer issues, politics, anti-capitalism, and classism. Examples of zines I’ve recently collected range from witchcraft and magic, football, cartoons, and Stonehenge. The presentation of these topics varies wildly and that’s part of the fascination and beauty. The appeal lies in their variety and individual uniqueness rather than the connection to a wider community of like-minded activists. Nowadays, we connect online (which is probably good, considering the whole Covid situation).

"Peaches (27965257275)" by Levi Manchak, licensed under CC BY 2.0

My interest in zines has become more of a personal one. I want to examine their history and function, whilst still keeping true to the content and aesthetics of zines. Ideally, the more amateur looking, the better. The more glue and sticky tape and frayed edges, the more unique and authentic they seem. But this ‘rubbishy’, throwaway stuff documents the time itself –as it happened – rather than the ‘whitewashed’ and ‘male’ versions of history that we get presented with. And when we look at something like feminism before the internet, we don’t want a ‘whitewashed’ or ‘male’ version because it’s not as if these female zinesters were asking for men’s permission when they made their DIY pamphlets about sex, gender, race, and ethnicity. So I decided to write a ‘meta-fanzine’, partially from my own time in the Ladyfest scenes, partially from collecting zines for their general weirdness. This novel in the form of a fanzine or a zine that’s aware of its own artificiality, tackles themes of gender, feminism, queer identity and race but is set in the 1990s before the internet was so widely available. This idea became my Ph.D. – a novel called Zazen that traces a Manson-style cult and the rise of a female-fronted Britpop band called Sequence – all through the lenses of mixed-race men, women journalists and zine writers. The novel itself is in a collage form – a mixture of zine pieces, demo reviews, readers’ letters, interviews, gig reviews, front covers, features articles, and fiction to illustrate how different events can be interpreted in different ways, thanks to the cultural positions of characters.

For me, a zines function might have changed over the decades, but the DIY ethos, the idea of not having to ‘ask for permission’ to create something that can challenge an accepted narrative is the most important legacy zines have left us with.

Sabrina Mei-Li Smith is a Ph.D. scholar, writer, lecturer, and researcher in the discipline of creative writing. She lectures on ‘Writing Identity’ and ‘Writing Place’ at De Montfort University’s undergraduate Creative Writing B.A. Her first play, The Holy Bible, received Arts Council funding and is a bioficiton piece about missing Manic Street Preachers guitarist Richey Edwards. She specialises in writing with marginalised individuals, and challenging accepted narratives, through her residencies with Writing East Midlands Elder Tree project, and Leicester City Council’s Memories into Healing Words project which documents the narratives of Leicester’s elderly, street-homeless, and Irish Traveller communities. She runs specialised and mainstream creative writing workshops for Leicester City Council’s Adult Education College and has been a writer in residence for Coalville Writes 2019. Sabrina was part of De Montfort University’s National Writing Day – Creative Writing and Practice Research Conference in 2020

SUPPORT INDEPENDENT FEMINIST MEDIA. SHOP NOW!

0 comments